Since the start of the 21st century, U.S. consumers have seen a divergence of price movements across various categories. Nowhere is this better illustrated than on this chart concept thought up by AEI’s Mark J. Perry. It’s sometimes referred to as the “chart of the century” because it provides such a clear and impactful jump-off point to discuss a number of economic forces. The punchline is that many consumer goods—particularly those that were easily outsourced—saw price drops, while key “non-tradable” categories saw massive increases. We’ll look at both situations in more detail below.

Race to the Top: Inflation in Healthcare and Education

Since the beginning of this century, two types of essential categories have been marching steadily upward in price: healthcare and education. America has a well documented “medical inflation” issue. There are a number of reasons why costs in the healthcare sector keep rising, including rising labor costs, an aging population, better technology, and medical tourism. The pricing of pharmaceutical products and hospital services are also a major contributor to increases. As Barry Ritholtz has diplomatically stated, “market forces don’t work very well in this industry”. Rising medical costs have serious consequences for the U.S. population. Recent data indicates that half of Americans now carry medical debt, with the majority owing $1,000 or more. Also near the top of the chart are education-related categories. In the ’60s and ’70s, tuition roughly tracked with inflation, but that began to change in the mid-1980s. Since then, tuition costs have marched ever upward. Since 2000, tuition prices have increased by 178% and college textbooks have jumped 162%. As usual, low income students are disproportionally impacted by rising tuition. Pell Grants now cover a much smaller portion of tuition than they used to, and the majority of states have cut funding to higher education in recent years.

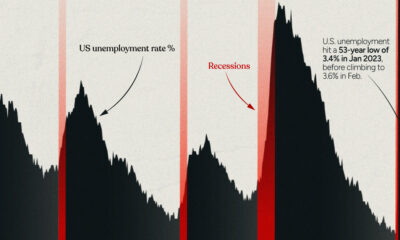

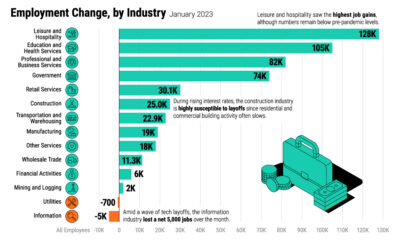

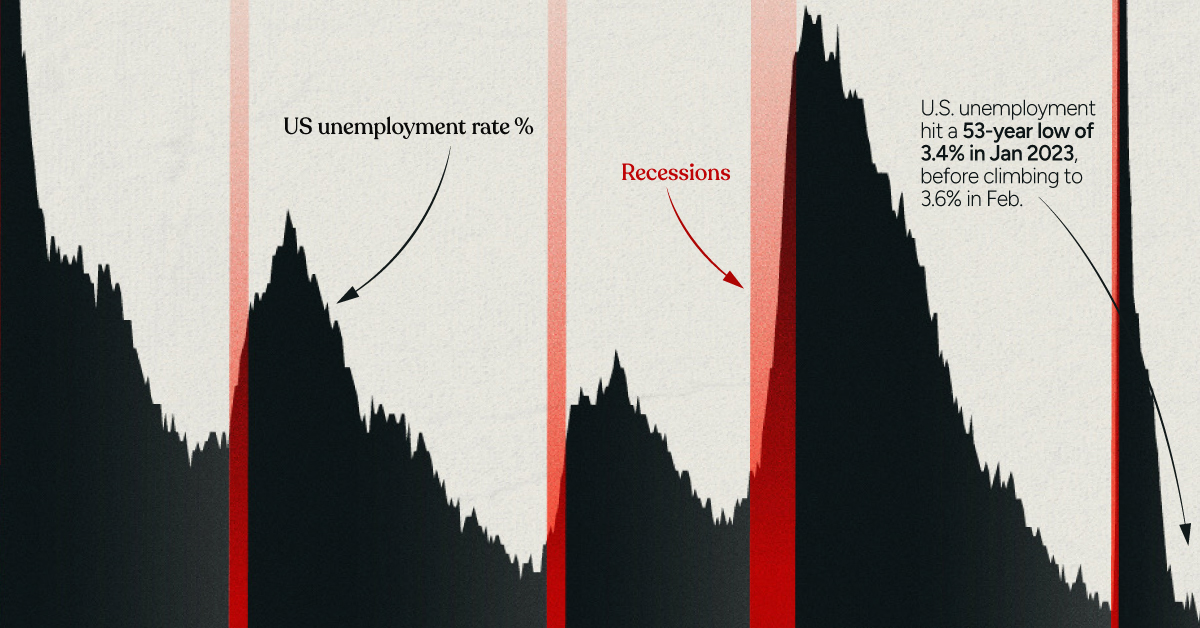

Globalization: A Tale of Televisions and Toys

Even though essentials like education and heathcare have rocketed up, it’s not all bad news. Consumers have seen the price of some goods and services drop dramatically. Flat screen televisions used to be a big ticket item. At the turn of the century, a flat screen TV would cost around 17% of the median income of the time ($42,148). In the early aughts though, prices began to fall quickly. Today, a new TV will cost less than 1% of the U.S. median income ($54,132). Similarly, cellular services and software have gotten cheaper over the past two decades as well. Toys are another prime example. Not only are most toys manufactured overseas, the value proposition has changed as children have new digital options to entertain themselves with. Over a long-term perspective, items like clothing and household furnishings have remained relatively flat in price, even after the most recent bout of inflation. on Both figures surpassed analyst expectations by a wide margin, and in January, the unemployment rate hit a 53-year low of 3.4%. With the recent release of February’s numbers, unemployment is now reported at a slightly higher 3.6%. A low unemployment rate is a classic sign of a strong economy. However, as this visualization shows, unemployment often reaches a cyclical low point right before a recession materializes.

Reasons for the Trend

In an interview regarding the January jobs data, U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen made a bold statement: While there’s nothing wrong with this assessment, the trend we’ve highlighted suggests that Yellen may need to backtrack in the near future. So why do recessions tend to begin after unemployment bottoms out?

The Economic Cycle

The economic cycle refers to the economy’s natural tendency to fluctuate between periods of growth and recession. This can be thought of similarly to the four seasons in a year. An economy expands (spring), reaches a peak (summer), begins to contract (fall), then hits a trough (winter). With this in mind, it’s reasonable to assume that a cyclical low in the unemployment rate (peak employment) is simply a sign that the economy has reached a high point.

Monetary Policy

During periods of low unemployment, employers may have a harder time finding workers. This forces them to offer higher wages, which can contribute to inflation. For context, consider the labor shortage that emerged following the COVID-19 pandemic. We can see that U.S. wage growth (represented by a three-month moving average) has climbed substantially, and has held above 6% since March 2022. The Federal Reserve, whose mandate is to ensure price stability, will take measures to prevent inflation from climbing too far. In practice, this involves raising interest rates, which makes borrowing more expensive and dampens economic activity. Companies are less likely to expand, reducing investment and cutting jobs. Consumers, on the other hand, reduce the amount of large purchases they make. Because of these reactions, some believe that aggressive rate hikes by the Fed can either cause a recession, or make them worse. This is supported by recent research, which found that since 1950, central banks have been unable to slow inflation without a recession occurring shortly after.

Politicians Clash With Economists

The Fed has raised interest rates at an unprecedented pace since March 2022 to combat high inflation. More recently, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell warned that interest rates could be raised even higher than originally expected if inflation continues above target. Senator Elizabeth Warren expressed concern that this would cost Americans their jobs, and ultimately, cause a recession. Powell remains committed to bringing down inflation, but with the recent failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, some analysts believe there could be a pause coming in interest rate hikes. Editor’s note: just after publication of this article, it was confirmed that U.S. interest rates were hiked by 25 basis points (bps) by the Federal Reserve.