It’s a loaded question — as you’ll see, there is plenty of nuance involved in the answer. Depending on how you define things, there are many jurisdictions that can lay claim to this coveted title. Let’s dive into some of these technicalities, and then we can provide context for how we’ve defined democracy in today’s particular chart.

Laying the Claim

If you’re looking for the very first instance of democracy, credit is often attributed to Ancient Athens. It’s there the term originated, based on the Greek words demos (“common people”) and kratos (“strength”). In the 6th century BC, the city-state allowed all landowners to speak at the legislative assembly, blazing a path that would be followed by democracies in the future. However, Ancient Athens wasn’t really a country in the modern sense. It’s also not around anymore, so that certainly disqualifies the oldest continuous democratic country today. Iceland and the Isle of Man both have interesting claims to democracy. Each has a parliamentary body that is over 1,000 years old, making them the longest standing democratic institutions in the world. But Iceland only got its independence in 1944 from Denmark — and while it is self-governing, the Isle of Man is not a country. Of course, when we’re talking about democracy today, we’re really talking about universal suffrage. New Zealand may have the best claim here — by 1893, the self-governing colony allowed all women and ethnicities to vote in elections.

A Common Set of Criteria

While many civilizations, institutions, and societies have a rightful claim to contributing to democracy (including many we did not mention above), measuring the world’s oldest democracies today requires following a common set of criteria. In today’s chart, we used data from Boix, C., Miller, M., & Rosato, S. (2013, 2018), which looks at the age of democratic regimes for 219 countries since the year 1800. Countries are classified as democracies if they meet the following conditions: Democracies also have to be continuous in order to count. Although France has important democratic origins, the country is currently on its fifth republic since the French Revolution, thanks to Napoleon, Vichy France, and other instances where things went sideways. While the above criteria isn’t perfect, it does create a stable playing field to assess when countries adopted democratic systems in principle. (However, the exclusion of certain populations, notably women and specific ethnicities, in being given the right to vote, or to be elected to legislative assemblies, is another story).

The Oldest Democracies, by Number of Years

Using the above criteria, here is a list of the world’s 25 oldest democracies:

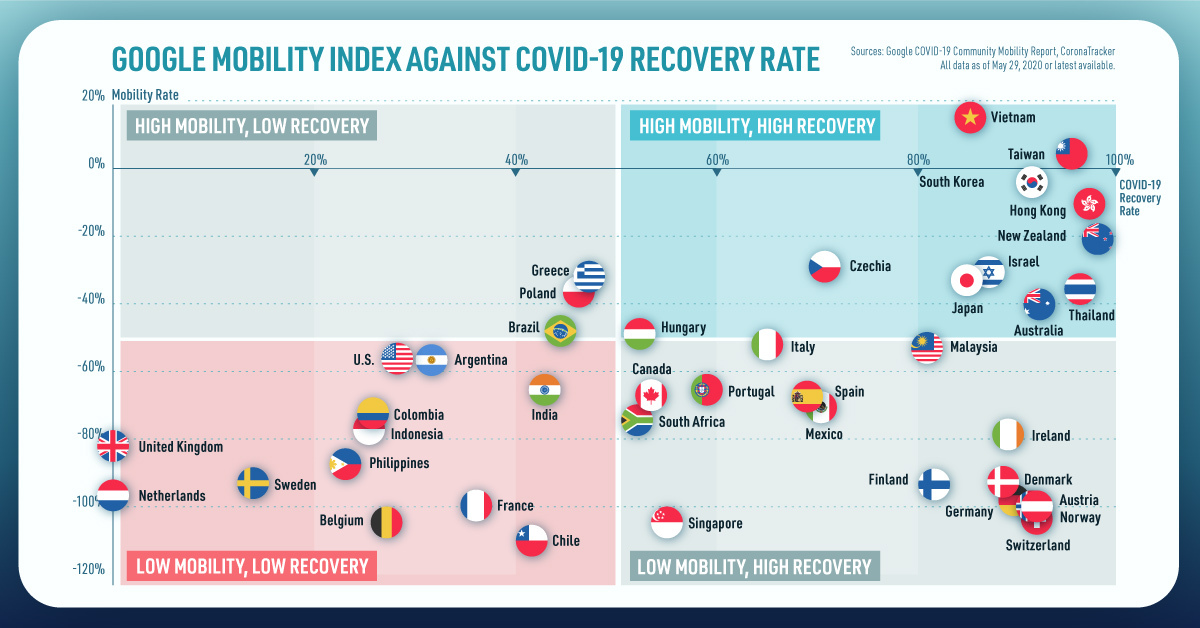

Using this specific criteria, there is only one country with continuous democracy for more than 200 years (The United States), and fourteen countries with democracies older than a century. As you’ll notice in the data, many countries became democracies after World War II. The Japanese Empire, for example, was occupied by Allied Forces and then dissolved. It then regained sovereignty afterwards, emerging as a newly democratic regime. Final notes: The data here goes back to 1800, and we have adjusted it to be current as of 2019. One change we made was to Tunisia, which is listed as the 24th oldest democracy in the data. Based on our due diligence on the subject, we felt it was appropriate to leave it off the list, given that most experts see the country as only achieving the status in 2014 in the post-Arab Spring era. on Today’s chart measures the extent to which 41 major economies are reopening, by plotting two metrics for each country: the mobility rate and the COVID-19 recovery rate: Data for the first measure comes from Google’s COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports, which relies on aggregated, anonymous location history data from individuals. Note that China does not show up in the graphic as the government bans Google services. COVID-19 recovery rates rely on values from CoronaTracker, using aggregated information from multiple global and governmental databases such as WHO and CDC.

Reopening Economies, One Step at a Time

In general, the higher the mobility rate, the more economic activity this signifies. In most cases, mobility rate also correlates with a higher rate of recovered people in the population. Here’s how these countries fare based on the above metrics. Mobility data as of May 21, 2020 (Latest available). COVID-19 case data as of May 29, 2020. In the main scatterplot visualization, we’ve taken things a step further, assigning these countries into four distinct quadrants:

1. High Mobility, High Recovery

High recovery rates are resulting in lifted restrictions for countries in this quadrant, and people are steadily returning to work. New Zealand has earned praise for its early and effective pandemic response, allowing it to curtail the total number of cases. This has resulted in a 98% recovery rate, the highest of all countries. After almost 50 days of lockdown, the government is recommending a flexible four-day work week to boost the economy back up.

2. High Mobility, Low Recovery

Despite low COVID-19 related recoveries, mobility rates of countries in this quadrant remain higher than average. Some countries have loosened lockdown measures, while others did not have strict measures in place to begin with. Brazil is an interesting case study to consider here. After deferring lockdown decisions to state and local levels, the country is now averaging the highest number of daily cases out of any country. On May 28th, for example, the country had 24,151 new cases and 1,067 new deaths.

3. Low Mobility, High Recovery

Countries in this quadrant are playing it safe, and holding off on reopening their economies until the population has fully recovered. Italy, the once-epicenter for the crisis in Europe is understandably wary of cases rising back up to critical levels. As a result, it has opted to keep its activity to a minimum to try and boost the 65% recovery rate, even as it slowly emerges from over 10 weeks of lockdown.

4. Low Mobility, Low Recovery

Last but not least, people in these countries are cautiously remaining indoors as their governments continue to work on crisis response. With a low 0.05% recovery rate, the United Kingdom has no immediate plans to reopen. A two-week lag time in reporting discharged patients from NHS services may also be contributing to this low number. Although new cases are leveling off, the country has the highest coronavirus-caused death toll across Europe. The U.S. also sits in this quadrant with over 1.7 million cases and counting. Recently, some states have opted to ease restrictions on social and business activity, which could potentially result in case numbers climbing back up. Over in Sweden, a controversial herd immunity strategy meant that the country continued business as usual amid the rest of Europe’s heightened regulations. Sweden’s COVID-19 recovery rate sits at only 13.9%, and the country’s -93% mobility rate implies that people have been taking their own precautions.

COVID-19’s Impact on the Future

It’s important to note that a “second wave” of new cases could upend plans to reopen economies. As countries reckon with these competing risks of health and economic activity, there is no clear answer around the right path to take. COVID-19 is a catalyst for an entirely different future, but interestingly, it’s one that has been in the works for a while. —Carmen Reinhart, incoming Chief Economist for the World Bank Will there be any chance of returning to “normal” as we know it?