In many Western countries, it’s easy to take press freedom for granted. Instances of fake news, clickbait, and hyper-partisan reporting are points of consternation in the modern media landscape, and can sometimes overshadow the greater good that unrestricted journalism provides to society. Of course, the ability to do that important work can vary significantly around the world. Being an investigative journalist in Sweden comes with a very different set of circumstances and considerations than doing the same thing in a country such as Saudi Arabia or Venezuela. Today’s map highlights the results of the 2020 Global Press Freedom Index, produced by Reporters Without Borders. The report looks at press freedom in 180 countries and territories.

A Profession Not Without Its Risks

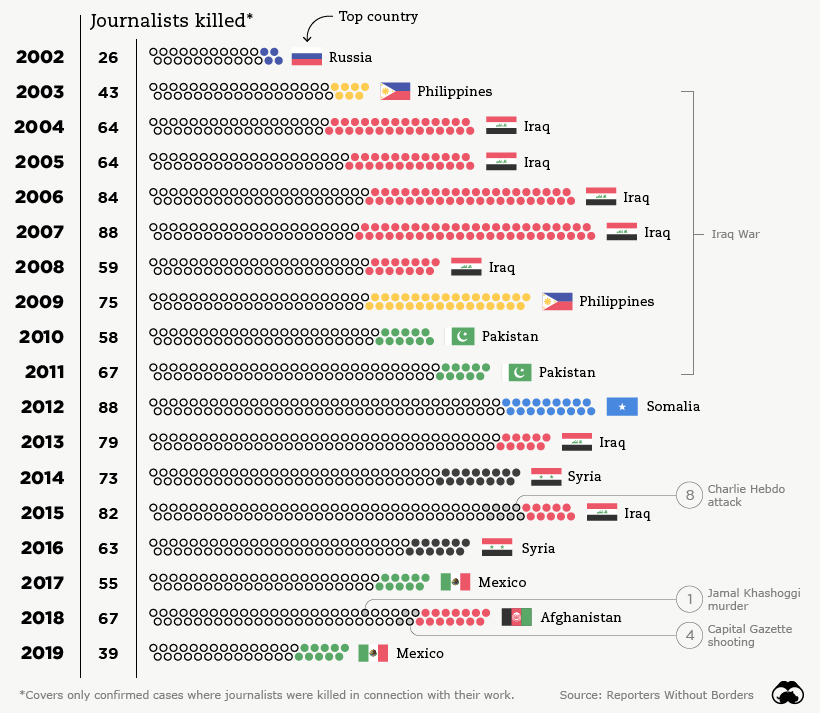

Today, nearly 75% of countries are in categories that the report describes as problematic, difficult, and very serious. While these negative forces often come in the form of censorship and intimidation, journalism can be a risky profession in some of the more restrictive countries. One example is Mexico, where nearly 60 journalists were killed as a direct result of their reporting over the last decade.

There is good news though: the number of journalists killed last year was the lowest since the report began in 2002. Even better, press freedom scores increased around the world in the 2020 report.

Press Freedom: The Good, The Bad, The Ugly

Here are the scores for all 180 countries and territories covered in the report, sorted by 2020 ranking and score: Which countries stood out in this year’s edition of the press freedom rankings? Norway: Nordic Countries have topped the Press Freedom Index since its inception, and Norway (Rank: #1) in particular is an example for the world. Despite a very free media environment, the government recently mandated a commission to conduct a comprehensive review of the conditions for freedom of speech. Members will consider measures to promote the broadest possible participation in the public debate, and means to hamper the spread of fake news and hate speech. Malaysia: A new government ushered in a less restrictive era in Malaysia in 2018. Journalists and media outlets that had been blacklisted were able to resume working, and anti-fake news laws that were viewed as problematic were repealed. As a result, Malaysia’s index score has improved by 15 points in the past two years. This is in sharp contrast to neighbor, Singapore, which is ranked 158th out of 180 countries. Ethiopia: When Abiy Ahmed Ali took power in Africa’s second most populous country in 2018, his government restored access to over 200 news websites and blogs that had been previously blocked. As well, many detained journalists and bloggers were released as the chill over the country’s highly restrictive media environment began to thaw. As a result, Ethiopia (#99) jumped up eleven spots in the Press Freedom Index in 2020. The Middle East: Though the situation in this region has begun to stabilize somewhat, restrictions still remain – even in relatively safe and stable countries. Both Saudi Arabia (#170) and Egypt (#166) have imprisoned a number of journalists in recent years, and the former is still dealing with the reputational fallout from the assassination of Saudi dissident and Washington Post columnist, Jamal Khashoggi. China: Sitting near the bottom of the list is China (#176). More than 100 journalists and bloggers are currently detained as the country maintains a tight grip over the press – particularly as COVID-19 began to spread. Earlier this year, the Chinese government also expelled over a dozen journalists representing U.S. publications.

2020: A Pivotal Year for the Press

As the world grapples with a deadly pandemic, a global economic shutdown, and a crucial election year, the media could find itself in the spotlight more than in previous years. How the stories of 2020 are told will influence our collective future – and how regimes choose to treat journalists under this atypical backdrop will tell us a lot about press freedom going forward. on Even while political regimes across these countries have changed over time, they’ve largely followed a few different types of governance. Today, every country can ultimately be classified into just nine broad forms of government systems. This map by Truman Du uses information from Wikipedia to map the government systems that rule the world today.

Countries By Type of Government

It’s important to note that this map charts government systems according to each country’s legal framework. Many countries have constitutions stating their de jure or legally recognized system of government, but their de facto or realized form of governance may be quite different. Here is a list of the stated government system of UN member states and observers as of January 2023: Let’s take a closer look at some of these systems.

Monarchies

Brought back into the spotlight after the death of Queen Elizabeth II of England in September 2022, this form of government has a single ruler. They carry titles from king and queen to sultan or emperor, and their government systems can be further divided into three modern types: constitutional, semi-constitutional, and absolute. A constitutional monarchy sees the monarch act as head of state within the parameters of a constitution, giving them little to no real power. For example, King Charles III is the head of 15 Commonwealth nations including Canada and Australia. However, each has their own head of government. On the other hand, a semi-constitutional monarchy lets the monarch or ruling royal family retain substantial political powers, as is the case in Jordan and Morocco. However, their monarchs still rule the country according to a democratic constitution and in concert with other institutions. Finally, an absolute monarchy is most like the monarchies of old, where the ruler has full power over governance, with modern examples including Saudi Arabia and Vatican City.

Republics

Unlike monarchies, the people hold the power in a republic government system, directly electing representatives to form government. Again, there are multiple types of modern republic governments: presidential, semi-presidential, and parliamentary. The presidential republic could be considered a direct progression from monarchies. This system has a strong and independent chief executive with extensive powers when it comes to domestic affairs and foreign policy. An example of this is the United States, where the President is both the head of state and the head of government. In a semi-presidential republic, the president is the head of state and has some executive powers that are independent of the legislature. However, the prime minister (or chancellor or equivalent title) is the head of government, responsible to the legislature along with the cabinet. Russia is a classic example of this type of government. The last type of republic system is parliamentary. In this system, the president is a figurehead, while the head of government holds real power and is validated by and accountable to the parliament. This type of system can be seen in Germany, Italy, and India and is akin to constitutional monarchies. It’s also important to point out that some parliamentary republic systems operate slightly differently. For example in South Africa, the president is both the head of state and government, but is elected directly by the legislature. This leaves them (and their ministries) potentially subject to parliamentary confidence.

One-Party State

Many of the systems above involve multiple political parties vying to rule and govern their respective countries. In a one-party state, also called a single-party state or single-party system, only one political party has the right to form government. All other political parties are either outlawed or only allowed limited participation in elections. In this system, a country’s head of state and head of government can be executive or ceremonial but political power is constitutionally linked to a single political movement. China is the most well-known example of this government system, with the General Secretary of the Communist Party of China ruling as the de facto leader since 1989.

Provisional

The final form of government is a provisional government formed as an interim or transitional government. In this system, an emergency governmental body is created to manage political transitions after the collapse of a government, or when a new state is formed. Often these evolve into fully constitutionalized systems, but sometimes they hold power for longer than expected. Some examples of countries that are considered provisional include Libya, Burkina Faso, and Chad.