Many of the top websites in 1998 were news aggregators or search portals, which are easy concepts to understand. Today, brand touch-points are often spread out between devices (e.g. mobile apps vs. desktop) and a myriad of services and sub-brands (e.g. Facebook’s constellation of apps). As a result, the world’s biggest websites are complex, interconnected web properties. The visualization above, which primarily uses data from ComScore’s U.S. Multi-Platform Properties ranking, looks at which of the internet giants have evolved to stay on top, and which have faded into internet lore.

America Moves Online

For millions of curious people the late ’90s, the iconic AOL compact disc was the key that opened the door to the World Wide Web. At its peak, an estimated 35 million people accessed the internet using AOL, and the company rode the Dotcom bubble to dizzying heights, reaching a valuation of $222 billion dollars in 1999. AOL’s brand may not carry the caché it once did, but the brand never completely faded into obscurity. The company continually evolved, finally merging with Yahoo after Verizon acquired both of the legendary online brands. Verizon had high hopes for the company—called Oath—to evolve into a “third option” for advertisers and users who were fed up with Google and Facebook. Sadly, those ambitions did not materialize as planned. In 2019, Oath was renamed Verizon Media, and was eventually sold once again in 2021.

A City of Gifs and Web Logs

As internet usage began to reach critical mass, web hosts such as AngelFire and GeoCities made it easy for people to create a new home on the Web. GeoCities, in particular, made a huge impact on the early internet, hosting millions of websites and giving people a way to actually participate in creating online content. If it were a physical community of “home” pages, it would’ve been the third largest city in America, after Los Angeles. This early online community was at risk of being erased permanently when GeoCities was finally shuttered by Yahoo in 2009, but luckily, the nonprofit Internet Archive took special efforts to create a thorough record of GeoCities-hosted pages.

From A to Z

– New York Times (1998)

Digital Magazine Rack

Meredith will be an unfamiliar brand to many people looking at today’s top 20 list. While Meredith may not be a household name, the company controlled many of the country’s most popular magazine brands (People, AllRecipes, Martha Stewart, Health, etc.) including their sizable digital footprints. The company also owned a slew of local television networks around the United States. After its acquisition of Time Inc. in 2017, Meredith became the largest magazine publisher in the world. Since then, however, Meredith has divested many of its most valuable assets (Time, Sports Illustrated, Fortune). In December 2021, Meredith merged with IAC’s Dotdash.

“Hey, Google”

When people have burning questions, they increasingly turn to the internet for answers, but the diversity of sources for those answers is shrinking. Even as recently as 2013, we can see that About.com, Ask.com, and Answers.com were still among the biggest websites in America. Today though, Google appears to have cemented its status as a universal wellspring of answers. As smart speakers and voice assistants continue penetrate the market and influence search behavior, Google is unlikely to face any near-term competition from any company not already in the top 20 list.

New Kids on the Block

Social media has long since outgrown its fad stage and is now a common digital thread connecting people across the world. While Facebook rapidly jumped into the top 20 by 2007, other social media infused brands took longer to grow into internet giants. By 2018, Twitter, Snapchat, and Facebook’s umbrella of platforms were all in the top 20, and you can see a more detailed and up-to-date breakdown of the social media universe here.

A Tangled Web

Today’s internet giants have evolved far beyond their ancestors from two decades ago. Many of the companies in the top 20 run numerous platforms and content streams, and more often than not, they are not household names. A few, such as Mediavine and CafeMedia, are services that manage ads. Others manage content distribution, such as music, or manage a constellation of smaller media properties, as is the case with Hearst. Lastly, there are still the tech giants. Remarkably, three of the top five web properties were in the top 20 list in 1998. In the fast-paced digital ecosystem, that’s some remarkable staying power. This article was inspired by an earlier work by Philip Bump, published in the Washington Post. on But fast forward to the end of last week, and SVB was shuttered by regulators after a panic-induced bank run. So, how exactly did this happen? We dig in below.

Road to a Bank Run

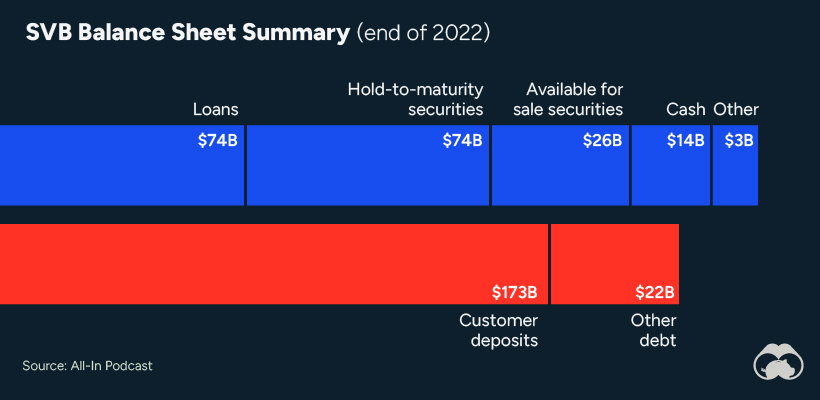

SVB and its customers generally thrived during the low interest rate era, but as rates rose, SVB found itself more exposed to risk than a typical bank. Even so, at the end of 2022, the bank’s balance sheet showed no cause for alarm.

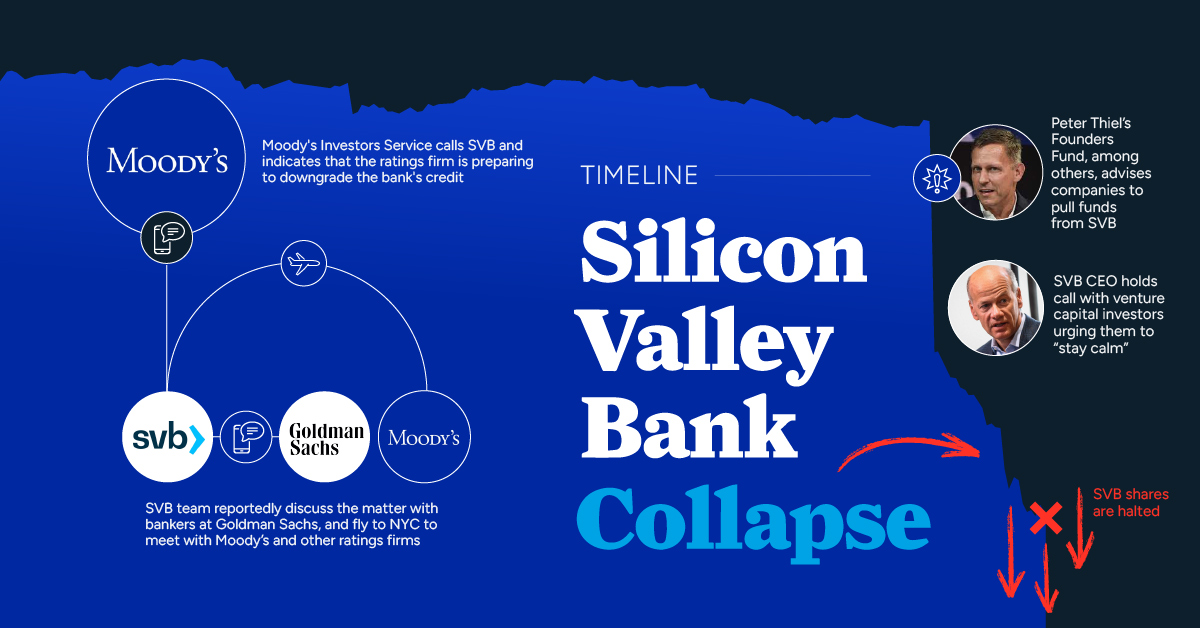

As well, the bank was viewed positively in a number of places. Most Wall Street analyst ratings were overwhelmingly positive on the bank’s stock, and Forbes had just added the bank to its Financial All-Stars list. Outward signs of trouble emerged on Wednesday, March 8th, when SVB surprised investors with news that the bank needed to raise more than $2 billion to shore up its balance sheet. The reaction from prominent venture capitalists was not positive, with Coatue Management, Union Square Ventures, and Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund moving to limit exposure to the 40-year-old bank. The influence of these firms is believed to have added fuel to the fire, and a bank run ensued. Also influencing decision making was the fact that SVB had the highest percentage of uninsured domestic deposits of all big banks. These totaled nearly $152 billion, or about 97% of all deposits. By the end of the day, customers had tried to withdraw $42 billion in deposits.

What Triggered the SVB Collapse?

While the collapse of SVB took place over the course of 44 hours, its roots trace back to the early pandemic years. In 2021, U.S. venture capital-backed companies raised a record $330 billion—double the amount seen in 2020. At the time, interest rates were at rock-bottom levels to help buoy the economy. Matt Levine sums up the situation well: “When interest rates are low everywhere, a dollar in 20 years is about as good as a dollar today, so a startup whose business model is “we will lose money for a decade building artificial intelligence, and then rake in lots of money in the far future” sounds pretty good. When interest rates are higher, a dollar today is better than a dollar tomorrow, so investors want cash flows. When interest rates were low for a long time, and suddenly become high, all the money that was rushing to your customers is suddenly cut off.” Source: Pitchbook Why is this important? During this time, SVB received billions of dollars from these venture-backed clients. In one year alone, their deposits increased 100%. They took these funds and invested them in longer-term bonds. As a result, this created a dangerous trap as the company expected rates would remain low. During this time, SVB invested in bonds at the top of the market. As interest rates rose higher and bond prices declined, SVB started taking major losses on their long-term bond holdings.

Losses Fueling a Liquidity Crunch

When SVB reported its fourth quarter results in early 2023, Moody’s Investor Service, a credit rating agency took notice. In early March, it said that SVB was at high risk for a downgrade due to its significant unrealized losses. In response, SVB looked to sell $2 billion of its investments at a loss to help boost liquidity for its struggling balance sheet. Soon, more hedge funds and venture investors realized SVB could be on thin ice. Depositors withdrew funds in droves, spurring a liquidity squeeze and prompting California regulators and the FDIC to step in and shut down the bank.

What Happens Now?

While much of SVB’s activity was focused on the tech sector, the bank’s shocking collapse has rattled a financial sector that is already on edge.

The four biggest U.S. banks lost a combined $52 billion the day before the SVB collapse. On Friday, other banking stocks saw double-digit drops, including Signature Bank (-23%), First Republic (-15%), and Silvergate Capital (-11%).

Source: Morningstar Direct. *Represents March 9 data, trading halted on March 10.

When the dust settles, it’s hard to predict the ripple effects that will emerge from this dramatic event. For investors, the Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen announced confidence in the banking system remaining resilient, noting that regulators have the proper tools in response to the issue.

But others have seen trouble brewing as far back as 2020 (or earlier) when commercial banking assets were skyrocketing and banks were buying bonds when rates were low.