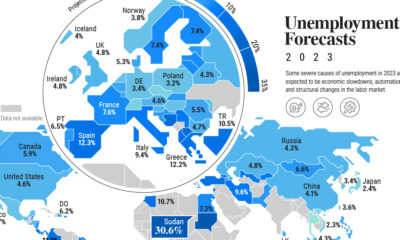

This interactive chart from the International Labour Organization (ILO) reveals how the global pandemic has affected both nominal and real wages, as well as unemployment rates. The date of data collection varies on a country-by-country basis, using the most recent available data. The most recent measurement of wage indices is from September 2020 in some countries and the least recent available data comes from Q2’2020. In select countries the date of unemployment rates and wage indices are different. As a point of reference, the average wage index in 2019 was 100. Note: the ILO uses national statistics databases and only the select countries had enough recent, available data for all three elements: nominal wages, real wages, and unemployment.

Where Average Wages are Falling

Average wages in many countries either plateaued or decreased significantly during the global pandemic. Sharp declines happened across a number of European countries, as well as in South Africa and Japan, for example.

Falling wages, however, do not necessarily mean that people are receiving less money, as many subsidies have been put in place to help cushion income or job loss. In many cases where wage indices declined, employment did not. This is because different job retention schemes were put in place, wherein workers were furloughed, but were given a portion of their wages from the national government. This allowed unemployment rates to remain steady while wages tapered off. In Europe, where wages have dropped considerably in many countries, wage subsidies have compensated for nearly 40% of wage bill loss in select countries. But while high income countries can afford to inject stimulus into their economies, most lower income countries cannot. This has come to be described as the fiscal stimulus gap.

Where Average Wages are Rising

While perhaps counterintuitive, rising average wages are in no way an inherent sign of a recovering economy or labor market. Regardless, when compared to 2019, wages have actually increased in the majority of countries, such as Brazil, Canada, United States, Italy, and the UK.

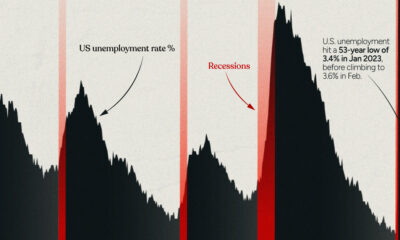

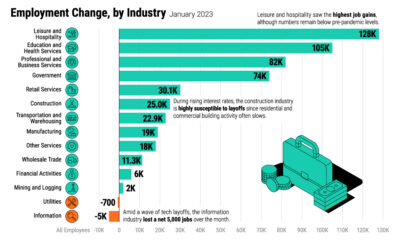

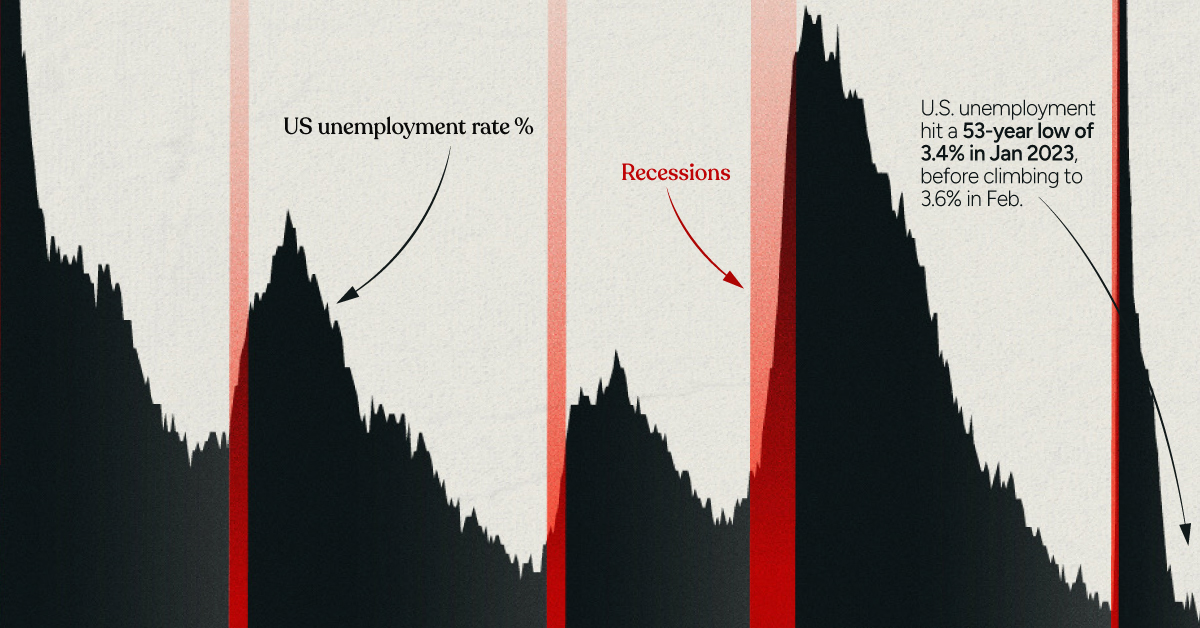

One reason for higher average wages is something called the compositional effect. The compositional effect is what occurs when wages are not actually increasing, but the makeup of employment changes. For example, the loss and subsequent absence of many lower paying jobs from the labor market due to COVID-19 can skew the average wage upwards. Brazil is a prime example of the compositional effect. As both nominal and real wages increase, so does unemployment. Brazil’s current unemployment rate is 13.3%, while wages have skyrocketed to a real wage index of 107.3 during the first half of 2020. The loss of these lower paying jobs has been extremely widespread, most negatively impacting informal workers, self-employed vendors, and migrant workers. Some policymakers have seen this as an opportunity to call for universal basic income. Even with job retention schemes to keep unemployment steady, many people are earning far less income and may never return to normal working hours in their current positions. on Both figures surpassed analyst expectations by a wide margin, and in January, the unemployment rate hit a 53-year low of 3.4%. With the recent release of February’s numbers, unemployment is now reported at a slightly higher 3.6%. A low unemployment rate is a classic sign of a strong economy. However, as this visualization shows, unemployment often reaches a cyclical low point right before a recession materializes.

Reasons for the Trend

In an interview regarding the January jobs data, U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen made a bold statement: While there’s nothing wrong with this assessment, the trend we’ve highlighted suggests that Yellen may need to backtrack in the near future. So why do recessions tend to begin after unemployment bottoms out?

The Economic Cycle

The economic cycle refers to the economy’s natural tendency to fluctuate between periods of growth and recession. This can be thought of similarly to the four seasons in a year. An economy expands (spring), reaches a peak (summer), begins to contract (fall), then hits a trough (winter). With this in mind, it’s reasonable to assume that a cyclical low in the unemployment rate (peak employment) is simply a sign that the economy has reached a high point.

Monetary Policy

During periods of low unemployment, employers may have a harder time finding workers. This forces them to offer higher wages, which can contribute to inflation. For context, consider the labor shortage that emerged following the COVID-19 pandemic. We can see that U.S. wage growth (represented by a three-month moving average) has climbed substantially, and has held above 6% since March 2022. The Federal Reserve, whose mandate is to ensure price stability, will take measures to prevent inflation from climbing too far. In practice, this involves raising interest rates, which makes borrowing more expensive and dampens economic activity. Companies are less likely to expand, reducing investment and cutting jobs. Consumers, on the other hand, reduce the amount of large purchases they make. Because of these reactions, some believe that aggressive rate hikes by the Fed can either cause a recession, or make them worse. This is supported by recent research, which found that since 1950, central banks have been unable to slow inflation without a recession occurring shortly after.

Politicians Clash With Economists

The Fed has raised interest rates at an unprecedented pace since March 2022 to combat high inflation. More recently, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell warned that interest rates could be raised even higher than originally expected if inflation continues above target. Senator Elizabeth Warren expressed concern that this would cost Americans their jobs, and ultimately, cause a recession. Powell remains committed to bringing down inflation, but with the recent failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, some analysts believe there could be a pause coming in interest rate hikes. Editor’s note: just after publication of this article, it was confirmed that U.S. interest rates were hiked by 25 basis points (bps) by the Federal Reserve.