Every year, it’s assembled by the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, a research center founded by UC Berkeley and funded primarily by the U.S. Department of Energy. The ambitious aim is to chart all U.S. energy use in one Sankey diagram, including the original energy source (i.e. nuclear, oil, wind, etc.) as well as the ultimate end use (i.e. residential, commercial, etc.) for the energy that was generated.

U.S. Energy Use in 2018

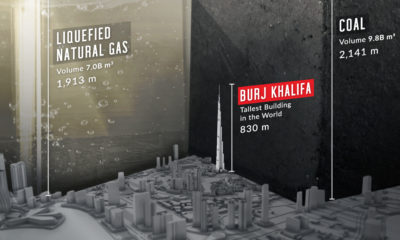

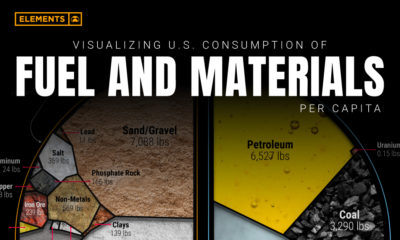

According to the research center’s most recent published version of the diagram, U.S. energy use totaled 101.2 quads in 2018. In case you are wondering, a single quad is equal to 1 quadrillion BTUs, with each quad being roughly equivalent to 185 million barrels of crude oil, 8 billion gallons of gasoline, or 1 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. Here is how the recent figure compares to previous years: As you can see in the table, U.S. energy use has been generally increasing, eventually topping 100 quads per year by 2018. During this time, the total percentage of fossil fuels in the mix has dropped, but only from 81.6% to 80.2%. Taking a closer look at the data, we can see that the largest percentage increases in the mix have come from solar and wind sources: Energy use measured in quads (1 quadrillion BTUs) Solar use has increased 122% since 2014, while wind jumped 46% over the same timeframe. Not surprisingly, energy derived from coal has fallen by 26%.

Dealing With the Rejects

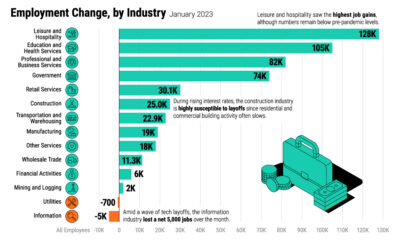

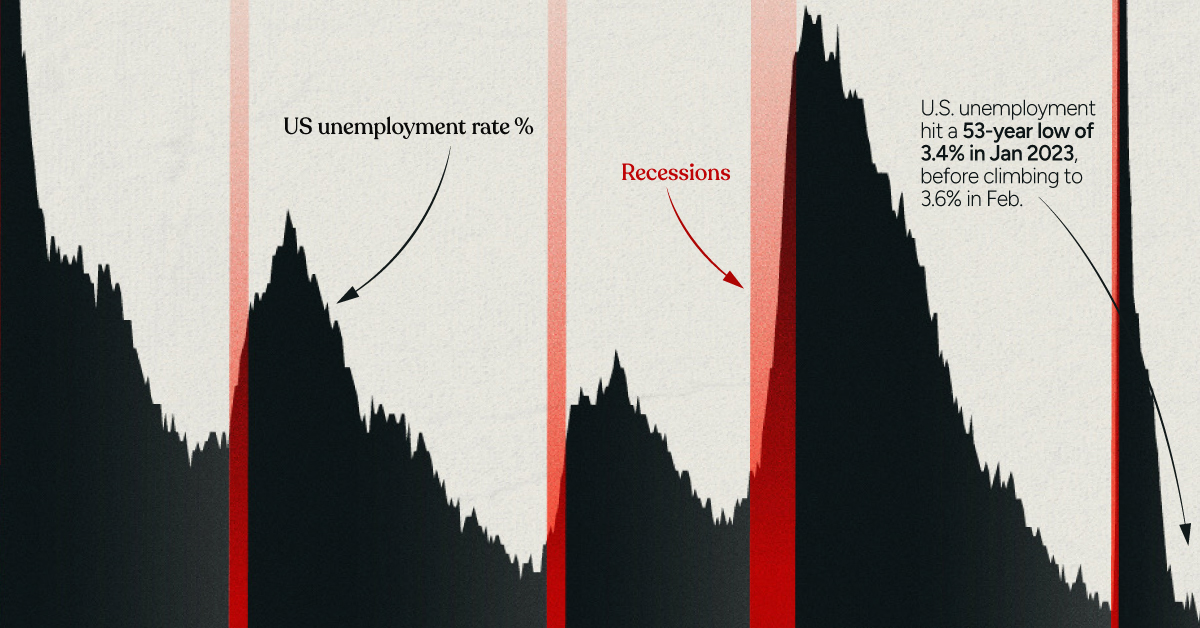

One interesting thing about the diagram is that it also shows rejected energy, which represents the energy that actually gets wasted due to various inefficiencies. In fact, 68% of all energy generated is not harnessed for any productive use. This makes sense, since gasoline engines are usually only about 20-40% efficient, and even electric engines are 85-90% efficient. Put another way, a certain percentage of energy is always released as heat, sound, light, or other forms that are hard for us to harness. As electric cars rise in popularity and as modern gas-powered engines also get more efficient, there is hope that the amount of this rejected energy will decrease over time. on Both figures surpassed analyst expectations by a wide margin, and in January, the unemployment rate hit a 53-year low of 3.4%. With the recent release of February’s numbers, unemployment is now reported at a slightly higher 3.6%. A low unemployment rate is a classic sign of a strong economy. However, as this visualization shows, unemployment often reaches a cyclical low point right before a recession materializes.

Reasons for the Trend

In an interview regarding the January jobs data, U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen made a bold statement: While there’s nothing wrong with this assessment, the trend we’ve highlighted suggests that Yellen may need to backtrack in the near future. So why do recessions tend to begin after unemployment bottoms out?

The Economic Cycle

The economic cycle refers to the economy’s natural tendency to fluctuate between periods of growth and recession. This can be thought of similarly to the four seasons in a year. An economy expands (spring), reaches a peak (summer), begins to contract (fall), then hits a trough (winter). With this in mind, it’s reasonable to assume that a cyclical low in the unemployment rate (peak employment) is simply a sign that the economy has reached a high point.

Monetary Policy

During periods of low unemployment, employers may have a harder time finding workers. This forces them to offer higher wages, which can contribute to inflation. For context, consider the labor shortage that emerged following the COVID-19 pandemic. We can see that U.S. wage growth (represented by a three-month moving average) has climbed substantially, and has held above 6% since March 2022. The Federal Reserve, whose mandate is to ensure price stability, will take measures to prevent inflation from climbing too far. In practice, this involves raising interest rates, which makes borrowing more expensive and dampens economic activity. Companies are less likely to expand, reducing investment and cutting jobs. Consumers, on the other hand, reduce the amount of large purchases they make. Because of these reactions, some believe that aggressive rate hikes by the Fed can either cause a recession, or make them worse. This is supported by recent research, which found that since 1950, central banks have been unable to slow inflation without a recession occurring shortly after.

Politicians Clash With Economists

The Fed has raised interest rates at an unprecedented pace since March 2022 to combat high inflation. More recently, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell warned that interest rates could be raised even higher than originally expected if inflation continues above target. Senator Elizabeth Warren expressed concern that this would cost Americans their jobs, and ultimately, cause a recession. Powell remains committed to bringing down inflation, but with the recent failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank, some analysts believe there could be a pause coming in interest rate hikes. Editor’s note: just after publication of this article, it was confirmed that U.S. interest rates were hiked by 25 basis points (bps) by the Federal Reserve.