The International Olympics Committee (IOC) partly reinforces this, as it doesn’t pay its participating sportspeople anything. But for those athletes going for the gold, silver, and bronze, the sweet sense of achievement that comes with winning a medal is sometimes accompanied by a big check—though these prizes don’t come from the IOC either.

The Winners Take It All

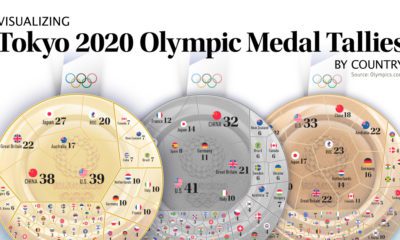

For placing at the podium and bringing home a medal, some countries promise their athletes significant bonuses—shooting as high as a six-figure range. For winning a gold medal, athletes from Singapore can earn up to SGD$1 million, or about $737,000. This reward is nearly 20 times the $37,500 that U.S. athletes pocket for the same achievement. However, the immense difference in payout makes sense if you consider what’s at stake. The U.S. typically dominates the leaderboard every year, and sheer numbers are a big part of this. At Tokyo 2020, Singapore only had 23 athletes representing the city-state across 12 events. In comparison, the U.S. brought along the biggest contingent of 657 athletes participating in 44 events. Here are the 12 countries that boast largest monetary bonuses per medal: Correction: Another country that recently announced it would pay its athletes handsomely is Indonesia—a 5 billion rupiah cash reward translates into $349,000 for winning gold. In several of these countries, these USD-value wins translate to even higher earnings back home. For example, $1 is equivalent to nearly 425 Kazakhstani tenge, or about 50.5 Philippine pesos. Hidilyn Diaz of The Philippines won her country’s first ever gold medal at Tokyo 2020, in the women’s 55kg weightlifting category. At Rio 2016, she also historically broke a 20-year dry spell for the nation and won a silver medal. Another way that athletes can gain value from winning a medal is by scoring endorsements with major brands. Often, these deal amounts far surpass any medal bonus—U.S. gymnast Simon Biles earns at least $5 million annually from sponsorships alone.

Some Strings Attached

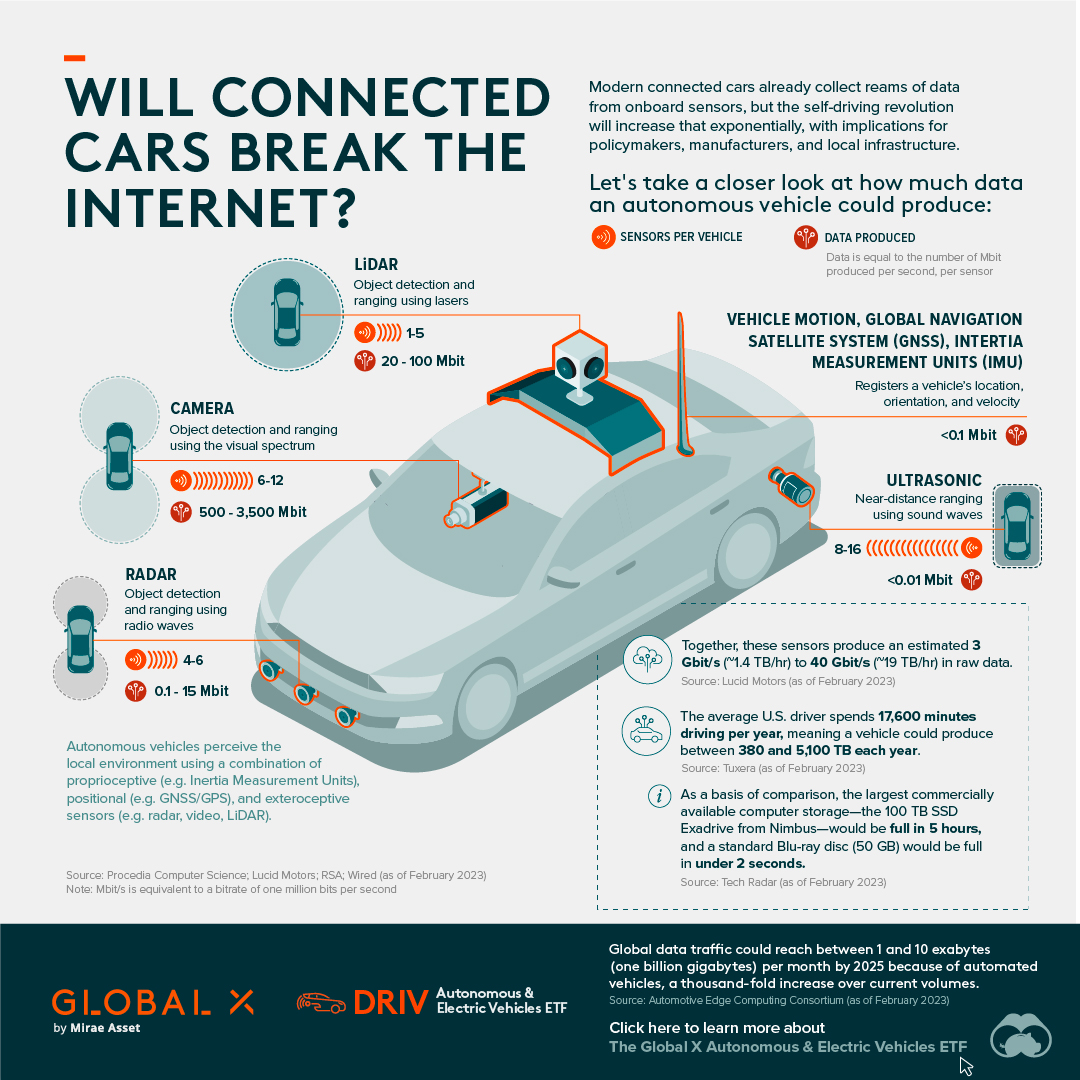

Why do countries award such big medal bonuses? When a country’s athletics are not driven by the private sector, and instead funded by the government, these monetary rewards help to encourage a stronger sports culture. In addition, the prize money is taxable in many cases—reinvesting the money into respective countries’ sports associations, and effectively giving back to the community. on Today’s connected cars come stocked with as many as 200 onboard sensors, tracking everything from engine temperature to seatbelt status. And all those sensors create reams of data, which will increase exponentially as the autonomous driving revolution gathers pace. With carmakers planning on uploading 50-70% of that data, this has serious implications for policymakers, manufacturers, and local network infrastructure. In this visualization from our sponsor Global X ETFs, we ask the question: will connected cars break the internet?

Data is a Plural Noun

Just how much data could it possibly be? There are lots of estimates out there, from as much as 450 TB per day for robotaxis, to as little as 0.383 TB per hour for a minimally connected car. This visualization adds up the outputs from sensors found in a typical connected car of the future, with at least some self-driving capabilities. The focus is on the kinds of sensors that an automated vehicle might use, because these are the data hogs. Sensors like the one that turns on your check-oil-light probably doesn’t produce that much data. But a 4K camera at 30 frames a second, on the other hand, produces 5.4 TB per hour. All together, you could have somewhere between 1.4 TB and 19 TB per hour. Given that U.S. drivers spend 17,600 minutes driving per year, a vehicle could produce between 380 and 5,100 TB every year. To put that upper range into perspective, the largest commercially available computer storage—the 100 TB SSD Exadrive from Nimbus—would be full in 5 hours. A standard Blu-ray disc (50 GB) would be full in under 2 seconds.

Lag is a Drag

The problem is twofold. In the first place, the internet is better at downloading than uploading. And this makes sense when you think about it. How often are you uploading a video, versus downloading or streaming one? Average global mobile download speeds were 30.78 MB/s in July 2022, against 8.55 MB/s for uploads. Fixed broadband is much higher of course, but no one is suggesting that you connect really, really long network cables to moving vehicles.

Ultimately, there isn’t enough bandwidth to go around. Consider the types of data traffic that a connected car could produce:

Vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) Vehicle-to-grid (V2G) Vehicles-to-people (V2P) Vehicles-to-infrastructure (V2I) Vehicles-to-everything (V2E)

The network just won’t be able to handle it.

Moreover, lag needs to be relatively non-existent for roads to be safe. If a traffic camera detects that another car has run a red light and is about to t-bone you, that message needs to get to you right now, not in a few seconds.

Full to the Gunwales

The second problem is storage. Just where is all this data supposed to go? In 2021, total global data storage capacity was 8 zettabytes (ZB) and is set to double to 16 ZB by 2025.

One study predicted that connected cars could be producing up to 10 exabytes per month, a thousand-fold increase over current data volumes.

At that rate, 8 ZB will be full in 2.2 years, which seems like a long time until you consider that we still need a place to put the rest of our data too.

At the Bleeding Edge

Fortunately, not all of that data needs to be uploaded. As already noted, automakers are only interested in uploading some of that. Also, privacy legislation in some jurisdictions may not allow highly personal data, like a car’s exact location, to be shared with manufacturers.

Uploading could also move to off-peak hours to even out demand on network infrastructure. Plug in your EV at the end of the day to charge, and upload data in the evening, when network traffic is down. This would be good for maintenance logs, but less useful for the kind of real-time data discussed above.

For that, Edge Computing could hold the answer. The Automotive Edge Computing Consortium has a plan for a next generation network based on distributed computing on localized networks. Storage and computing resources stay closer to the data source—the connected car—to improve response times and reduce bandwidth loads.

Invest in the Future of Road Transport

By 2030, 95% of new vehicles sold will be connected vehicles, up from 50% today, and companies are racing to meet the challenge, creating investing opportunities.

Learn more about the Global X Autonomous & Electric Vehicles ETF (DRIV). It provides exposure to companies involved in the development of autonomous vehicles, EVs, and EV components and materials.

And be sure to read about how experiential technologies like Edge Computing are driving change in road transport in Charting Disruption. This joint report by Global X ETFs and the Wall Street Journal is also available as a downloadable PDF.